A Rule by the Fish and Wildlife Service on 07/06/2022

AGENCY:

Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior.

ACTION:

Final rule.

SUMMARY:

We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), determine that the Canoe Creek clubshell ( Pleurobema athearni ), a freshwater mussel species endemic to a single watershed in north-central Alabama, is an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (Act), as amended. We also designate critical habitat for the species under the Act. In total, approximately 58.5 river kilometers (36.3 river miles) in St. Clair and Etowah Counties, Alabama, fall within the boundaries of the critical habitat designation. This rule extends the Act’s protections to the species and its designated critical habitat.

DATES:

This rule is effective August 5, 2022.

ADDRESSES:

This final rule is available on the internet at https://www.regulations.gov under Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2020-0078. Comments and materials we received, as well as supporting documentation we used in preparing this rule, are available for public inspection at https://www.regulations.gov at Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2020-0078.

The coordinates or plot points from which the maps are generated are included in the decision file for this critical habitat designation and are available at https://www.regulations.gov at Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2020-0078 and on the Service’s website at https://www.fws.gov/office/alabama-ecological-services. Any additional tools or supporting information that we developed for the critical habitat designation will also be available at the Service’s website set out above and may also be included in the preamble and at https://www.regulations.gov, or both.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

William J. Pearson, Field Supervisor, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Alabama Ecological Services Field Office, 1208 Main Street, Daphne, AL 36526; telephone 251-441-5181. Individuals in the United States who are deaf, deafblind, hard of hearing, or have a speech disability may dial 711 (TTY, TDD, or TeleBraille) to access telecommunications relay services. Individuals outside the United States should use the relay services offered within their country to make international calls to the point-of-contact in the United States.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Executive Summary

Why we need to publish a rule. Under the Act, a species warrants listing if it meets the definition of an endangered species (in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range) or a threatened species (likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range). We have determined that the Canoe Creek clubshell meets the definition of an endangered species; therefore, we are listing it as such. To the maximum extent prudent and determinable, we must designate critical habitat for any species that we determine to be an endangered or threatened species under the Act. Listing a species and designation of critical habitat can be completed only by issuing a rule.

What this document does. This rule lists the Canoe Creek clubshell ( Pleurobema athearni ) as an endangered species and designates critical habitat for this species under the Endangered Species Act. We are designating critical habitat in 2 units totaling approximately 58.5 river kilometers (km) (36.3 river miles (mi)) in St. Clair and Etowah Counties, Alabama.

The basis for our action. Under section 4(a)(1) of the Act, we may determine that a species is an endangered or threatened species based on any of five factors: (A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range; (B) overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) disease or predation; (D) the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or (E) other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence. We have determined that habitat degradation through changes in water quality and quantity (Factor A), increased sedimentation (Factor A), and climate events (Factor E) are the primary threats to the species.

Section 4(a)(3) of the Act requires the Secretary of the Interior (Secretary) to designate critical habitat concurrent with listing to the maximum extent prudent and determinable. Section 3(5)(A) of the Act defines critical habitat as (i) the specific areas within the geographical area occupied by the species, at the time it is listed, on which are found those physical or biological features (I) essential to the conservation of the species and (II) which may require special management considerations or protections; and (ii) specific areas outside the geographical area occupied by the species at the time it is listed, upon a determination by the Secretary that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species. Section 4(b)(2) of the Act states that the Secretary must make the designation on the basis of the best scientific data available and after taking into consideration the economic impact, the impact on national security, and any other relevant impacts of specifying any particular area as critical habitat.

Economic analysis. In accordance with section 4(b)(2) of the Act, we prepared an economic analysis of the impacts of designating critical habitat. We made the draft economic analysis available for public comments on November 3, 2020 (85 FR 69540).

Peer review and public comment. We sought the expert opinions of eight appropriate specialists with expertise in biology, habitat, and threats to the species regarding the species status assessment report. We did not receive any responses to our peer review requests. We also considered all comments and information we received from the public during the comment period for the proposed listing and critical habitat for the Canoe Creek clubshell.

Previous Federal Actions

On November 3, 2020, we published in the Federal Register a proposed rule (85 FR 69540) to list the Canoe Creek clubshell as an endangered species and to designate critical habitat for the species under the Act (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq. ). Please refer to that proposed ruled for a detailed description of other previous Federal actions concerning the Canoe Creek clubshell prior to the proposal’s publication.

Summary of Changes From the Proposed Rule

In preparing this final rule, we reviewed and fully considered comments from the public on our November 3, 2020, proposed rule regarding Canoe Creek clubshell (85 FR 69540). This final rule incorporates minor, non-substantive changes to the critical habitat unit descriptions (see Critical Habitat Designation) based on the comments we received. However, the information we received during the comment period for the proposed rule did not change our determination that the Canoe Creek clubshell is an endangered species.

Supporting Documents

A species status assessment (SSA) team prepared an SSA report for the Canoe Creek clubshell. The SSA team was composed of Service biologists, in consultation with other species experts. The SSA report represents a compilation of the best scientific and commercial data available concerning the status of the species, including the impacts of past, present, and future factors (both negative and beneficial) affecting the species. The SSA report and other materials relating to this rule can be found at https://www.regulations.gov under Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2020-0078.

Summary of Comments and Recommendations

In the November 3, 2020, proposed rule, we requested that interested parties submit written comments by January 4, 2021. We also contacted appropriate Federal and State agencies, scientific experts and organizations, and other interested parties and invited them to comment on the proposed rule. A newspaper notice inviting general public comment was published in the The St. Clair Times legal notice section on November 12, 2020. Although we invited requests for a public hearing in the rule, we did not receive any requests for a public hearing. All substantive information provided during the comment period has either been incorporated directly into this final determination, in the final economic analysis, or is addressed below.

Public Comments

We received 60 public comments in response to the proposed rule. We reviewed all comments we received during the public comment period for substantive issues and new information regarding the proposed rule. No new information concerning the proposed listing and designation of critical habitat for the Canoe Creek clubshell was received. Fifty-eight commenters were supportive of the proposal to list the Canoe Creek clubshell as endangered, to designate critical habitat, or both. Two commenters provided information about forestry practices but offered neither support nor opposition to the proposed rule. We did not receive any comments in opposition of the proposed rule. Below, we provide a summary of public comments we received; however, comments outside the scope of the proposed rule and those without supporting information did not warrant an explicit response and, thus, are not presented here. Identical or similar comments have been consolidated and a single response provided.

(1) Comment: One commenter indicated that the Service should consider forestry best management practices (BMPs) as part of the overall conservation benefit for the species and account for these beneficial actions in any threat analysis as done in past rules. A related comment recommended that the Service expressly recognize silviculture conducted in accordance with State-approved BMPs as a category of activities not expected to negatively impact the species’ conservation and recovery efforts in the final rule’s preamble and that these BMPs can ameliorate threats. Similarly, another commenter recommended the Service include a discussion of not only the ability of forest management to retain adequate conditions but also to improve forest conditions, which may redound to the benefit of species.

Our Response: We have considered the conservation benefits of implementing BMPs in our analyses. For example, in the SSA report, we explain that forestry BMPs will likely reduce sediments originating from forestry activities. We recognize that silvicultural operations (forestry activities) are widely implemented in accordance with State-approved best management practices (BMPs), and the adherence to these BMPs broadly protects water quality particularly related to sedimentation to an extent that does not impair the species’ conservation. Consistent with how we have addressed this issue in other relevant rules, we identified normal silvicultural practices that are carried out in accordance with BMPs as an example of an action that is unlikely to result in a violation of section 9 and the use of BMPs as an example of an activity that could ameliorate threats to physical and biological features essential to the conservation of the Canoe Creek clubshell. However, given the species’ low abundance and lack of successful reproduction and recruitment, the potential protection of water quality provided by BMPs do not appear to offset factors of decline. Therefore, we did not include a discussion of the ability of forest management to improve forest conditions to an extent that they may benefit the Canoe Creek clubshell.

(2) Comment: One commenter recommended that the description of designated critical habitat be clarified to state that critical habitat is limited to the bankfull width of the designated streams.

Our Response: We have clarified in this final rule that the boundaries of critical habitat extend laterally to the bankfull width. The critical habitat proposed for designation was not intended to include adjacent terrestrial components.

(3) Comment: One commenter recommended the Service note in the final rule its willingness to work collaboratively with forest owners adjacent to designated critical habitat to develop streamlined agreements, similar to Safe Harbor Agreements, that provided regulatory assurances to landowners and recognize that forest management conducted with approved BMPs will not be subject to enforcement under the prohibition on take in section 9 of the ESA.

Our Response: It is our mission to collaborate with public and private partners to conserve, protect, and enhance fish and wildlife and the habitats on which they depend. Tools are available through Section 10 of the Act for private landowners to coordinate with the Service to facilitate conservation of listed species and receive regulatory assurances and certainty for their actions. A discussion of these conservation tools is outside the scope of this rulemaking, but they will be identified and discussed in forthcoming recovery documents. We agree that when used and properly implemented, BMPs can offer a substantial improvement to water quality compared to forestry operations where BMPs are not properly implemented. Normal silvicultural practices that are carried out in accordance with BMPs as an action that can maintain favorable habitat conditions for the Canoe Creek clubshell. In addition, we recognize that silvicultural operations are widely implemented in accordance with State-approved best management practices (BMPs; as reviewed by Cristan et al. 2018, entire), and the adherence to these BMPs broadly protects water quality, particularly related to sedimentation (as reviewed by Cristan et al. 2016, entire; Warrington et al. 2017, entire; and Schilling et al. 2021, entire), to an extent that does not impair the species’ conservation. However, if adverse effects to listed species or critical habitat are likely or if take is reasonably certain to occur, formal consultation under section 7 with an accompanying biological opinion or a take permit under section 10 of the Act would be necessary to avoid violating section 9 of the Act.

I. Final Listing Determination

Background

The Canoe Creek clubshell is a narrow endemic mussel that is only known from the Big Canoe Creek watershed in St. Clair and Etowah counties, Alabama. The species’ current distribution is similar to its historical distribution, which has likely always been narrow. However, the current range of the species is disjunct; the eastern and western portions of its range are separated by a stretch of river that exceeds the dispersal distance of the species’ host fish (the clubshell’s primary mode of dispersal in the larval stage) and contains an inhabitable portion. As a result, we believe there is no genetic exchange occurring between the western and eastern portions of the species’ range and we characterize these portions as subpopulations.

Please refer to our November 3, 2020, proposed rule (85 FR 69540) and the species status assessment report (Service 2020, entire) for a summary of species background information.

Regulatory and Analytical Framework

Regulatory Framework

Section 4 of the Act (16 U.S.C. 1533) and its implementing regulations (50 CFR part 424) set forth the procedures for determining whether a species is an “endangered species” or a “threatened species.” The Act defines an “endangered species” as a species that is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range, and a “threatened species” as a species that is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range. The Act requires that we determine whether any species is an “endangered species” or a “threatened species” because of any of the following factors:

(A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range;

(B) Overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes;

(C) Disease or predation;

(D) The inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or

(E) Other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

These factors represent broad categories of natural or human-caused actions or conditions that could have an effect on a species’ continued existence. In evaluating these actions and conditions, we look for those that may have a negative effect on individuals of the species, as well as other actions or conditions that may ameliorate any negative effects or may have positive effects.

We use the term “threat” to refer in general to actions or conditions that are known to or are reasonably likely to negatively affect individuals of a species. The term “threat” includes actions or conditions that have a direct impact on individuals (direct impacts), as well as those that affect individuals through alteration of their habitat or required resources (stressors). The term “threat” may encompass—either together or separately—the source of the action or condition or the action or condition itself.

However, the mere identification of any threat(s) does not necessarily mean that the species meets the statutory definition of an “endangered species” or a “threatened species.” In determining whether a species meets either definition, we must evaluate all identified threats by considering the expected response by the species, and the effects of the threats—in light of those actions and conditions that will ameliorate the threats—on an individual, population, and species level. We evaluate each threat and its expected effects on the species, then analyze the cumulative effect of all of the threats on the species as a whole. We also consider the cumulative effect of the threats in light of those actions and conditions that will have positive effects on the species, such as any existing regulatory mechanisms or conservation efforts. The Secretary determines whether the species meets the definition of an “endangered species” or a “threatened species” only after conducting this cumulative analysis and describing the expected effect on the species now and in the foreseeable future.

The Act does not define the term “foreseeable future,” which appears in the statutory definition of “threatened species.” Our implementing regulations at 50 CFR 424.11(d) set forth a framework for evaluating the foreseeable future on a case-by-case basis. The term “foreseeable future” extends only so far into the future as the Services can reasonably determine that both the future threats and the species’ responses to those threats are likely. In other words, the foreseeable future is the period of time in which we can make reliable predictions. “Reliable” does not mean “certain”; it means sufficient to provide a reasonable degree of confidence in the prediction. Thus, a prediction is reliable if it is reasonable to depend on it when making decisions.

It is not always possible or necessary to define foreseeable future as a particular number of years. Analysis of the foreseeable future uses the best scientific and commercial data available and should consider the timeframes applicable to the relevant threats and to the species’ likely responses to those threats in view of its life-history characteristics. Data that are typically relevant to assessing the species’ biological response include species-specific factors such as lifespan, reproductive rates or productivity, certain behaviors, and other demographic factors.

Analytical Framework

The SSA report documents the results of our comprehensive biological review of the best scientific and commercial data regarding the status of the species, including an assessment of the potential threats to the species. The SSA report does not represent a decision by the Service on whether the species should be proposed for listing as an endangered or threatened species under the Act. It does, however, provide the scientific basis that informs our regulatory decisions, which involve the further application of standards within the Act and its implementing regulations and policies. The following is a summary of the key results and conclusions from the SSA report; the full SSA report can be found at Docket No. FWS-R4-ES-2020-0078 on https://www.regulations.gov.

To assess the Canoe Creek clubshell’s viability, we used the three conservation biology principles of resiliency, redundancy, and representation (Shaffer and Stein 2000, pp. 306-310). Briefly, resiliency supports the ability of the species to withstand environmental and demographic stochasticity ( e.g., wet or dry, warm or cold years), redundancy supports the ability of the species to withstand catastrophic events ( e.g., droughts, large pollution events), and representation supports the ability of the species to adapt over time to long-term changes in the environment ( e.g., climate changes). In general, the more resilient and redundant a species is and the more representation it has, the more likely it is to sustain populations over time, even under changing environmental conditions. Using these principles, we identified the species’ ecological requirements for survival and reproduction at the individual, population, and species levels, and described the beneficial and risk factors influencing the species’ viability.

The SSA process can be categorized into three sequential stages. During the first stage, we evaluated the individual species’ life-history needs. The next stage involved an assessment of the historical and current condition of the species’ demographics and habitat characteristics, including an explanation of how the species arrived at its current condition. The final stage of the SSA involved making predictions about the species’ responses to positive and negative environmental and anthropogenic influences. Throughout all of these stages, we used the best available information to characterize viability as the ability of a species to sustain populations in the wild over time. We use this information to inform our regulatory decision.

Summary of Biological Status and Threats

In this discussion, we review the biological condition of the species and its resources, and the threats that influence the species’ current and future condition, in order to assess the species’ overall viability and the risks to that viability.

Individual, Subpopulation, and Species Needs

Juvenile and adult Canoe Creek clubshells need stable instream substrates, including, but not limited to, coarse sand and gravel for settlement and sheltering. Clean, flowing water is needed to keep these substrates free from excess sedimentation that may reduce the amount of available habitat for sheltering, hinder a mussel’s ability to feed, and, in severe instances, cause smothering and death (see Risk Factors for the Canoe Creek Clubshell, below, for information on impacts of sedimentation). Clean, flowing water is also needed to attract host fish and disperse juveniles throughout stream reaches. In addition, freshwater mussels are sensitive to changes in water quality parameters such as temperature, dissolved oxygen, ammonia, and pollutants. Therefore, while the precise tolerance thresholds for these water quality parameters are unknown for the Canoe Creek clubshell, we know the species requires water of sufficient quality to sustain its natural physiological processes for normal behavior, growth, and survival at all life stages (see Risk Factors for the Canoe Creek Clubshell, below, for more information on water quality impairments). Food and nutrients are needed for individuals at all life stages for survival and growth. Lastly, the presence of host fish is needed for successful reproduction and dispersal. Host fish used by the Canoe Creek clubshell include the tricolor shiner ( Cyprinella trichroistia ), Alabama shiner ( C. callistia ), and striped shiner ( Luxilus chrysocephalus ), among others.

To be healthy at the subpopulation and species levels, the Canoe Creek clubshell needs individuals to be present in sufficient numbers throughout the subpopulations; reproduction, which is evidenced by the presence of multiple age classes within a subpopulation; and connectivity among mussel beds (local aggregations) within a subpopulation and between subpopulations. Mussel abundance facilitates reproduction. Mussels do not actively seek mates; males release sperm into the water column, where it drifts until a female takes it in (Moles and Layzer 2008, p. 212). Therefore, successful reproduction and subpopulation growth requires a sufficient number of females to be downstream of a sufficient number of males.

There must also be multiple mussel beds of sufficient density such that local stochastic events do not eliminate most or all the beds. Connectivity among beds within each subpopulation is also needed to allow mussel beds within a stream reach to be recolonized by one another and recover from stochastic events. A nonlinear distribution of beds over a sufficiently large area helps buffer against stochastic events that may impact portions of a clubshell subpopulation. Similarly, having multiple subpopulations that are connected to one another protects the species from catastrophic events, such as spills, because subpopulations can recolonize one another following events that impact the entirety or portions of one subpopulation.

Risk Factors for the Canoe Creek Clubshell

We identified several factors that are influencing the viability of the Canoe Creek clubshell. The primary factors include sedimentation, water quality, and climate events. For a complete discussion on the factors influencing the Canoe Creek clubshell, including the impacts of connectivity and conservation efforts, see the species status assessment report (Service 2020, pp. 30-53).

Sedimentation

Under a natural flow regime, sediments are washed through river and stream systems, and the overall amount of sediment in the substrate remains relatively stable over time. However, some past and ongoing activities or practices can result in elevated levels of sediment in the substrate. This excessive stream sedimentation (or siltation) can be caused by soil erosion associated with upland activities ( e.g., agriculture, poor forest management practices, unpaved roads, road construction, development, unstable streambanks, and urbanization) and stream channel destabilization associated with other activities ( e.g., dredging, poorly installed culverts, pipeline crossings, or other instream structures) (Brim Box and Mossa 1999, p. 102; Wynn et al. 2016, pp. 36-52). In severe cases, stream bottoms can become “embedded,” whereby substrate features including larger cobbles, gravel, and boulders are surrounded by, or buried in, sediment, which eliminates interstitial spaces (small openings between rocks and gravels).

The negative effects of increased sedimentation on mussels are relatively well-understood (Brim Box and Mossa 1999, entire; Gascho Landis et al. 2013, entire; Poole and Downing 2004, pp. 118-124). First, the river processes and sediment dynamics caused by increased sedimentation degrade and reduce the amount of habitat available to mussels. Juvenile mussels burrow into interstitial spaces in the substrate. Therefore, juveniles are particularly susceptible to excess sedimentation that removes those spaces, and they are unable to find adequate habitat to survive and become adults (Brim Box and Mossa 1999, p. 100). Second, sedimentation interferes with juvenile and adult physiological processes and behaviors. Mussels can die from being physically buried and smothered by excessive sediment. However, the primary impacts of excess sedimentation on individuals are sublethal; sedimentation can reduce a mussel’s ability to feed (Brim Box and Mossa 1999, p. 101) and reproduce (by reducing the success of glochidial attachment and metamorphosis; Beussink 2007, pp. 19-20).

The primary activities causing sedimentation that have occurred, and continue to occur, in the Big Canoe Creek watershed include urbanization and development, agricultural practices, and forest management (Wynn et al. 2016, pp. 9-10, 50-51). Approximately 59 percent of the Big Canoe Creek watershed is in evergreen or mixed deciduous forest, and forestry activities are common in central Big Canoe Creek and Little Canoe Creek West. Agriculture is also common, with pasture and small farms comprising 18 percent, and cultivated crops comprising 2.3 percent, of land use in the watershed. Urban development comprises 6 percent of the watershed’s land use and is concentrated near the cities of Ashville and Springville near the western clubshell subpopulation, and Steele near the eastern subpopulation (Wynn et al. 2016, p. 9).

A rapid habitat assessment survey that included an evaluation of sedimentation deposition was completed at multiple sites in the Big Canoe Creek watershed from 2008-2013 (Wynn et al. 2016, pp. 37-39). Overall habitat quality varied from poor to optimal throughout Big Canoe Creek’s nine subwatersheds, but six subwatersheds were reported impaired by sedimentation (Wynn et al. 2016, p. 51).

Water Quality

Water quality in freshwater systems can be impaired through contamination or alteration of water chemistry. Chemical contaminants are ubiquitous throughout the environment and are a major reason for the current declining status of freshwater mussel species nationwide (Augspurger et al. 2007, p. 2025). Chemicals such as ammonia enter the environment through both point and nonpoint discharges, including spills, industrial sources, municipal effluents, and agricultural runoff. These sources contribute organic compounds, heavy metals, pesticides, herbicides, and a wide variety of newly emerging contaminants to the aquatic environment.

Alteration of water chemistry parameters is another type of impairment. Reduced dissolved oxygen levels and increased water temperatures are of particular concern. Runoff and wastewater can wash nutrients ( e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus) into the water column, which can stimulate excessive plant growth (Carpenter et al. 1998, p. 561). The decomposition of this plant material can lead to reduced dissolved oxygen levels and eutrophication. Increased temperatures from climate changes (Alder and Hostetler 2013, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) National Climate Change Viewer) and low flow events during periods of drought can also reduce dissolved oxygen levels (Haag and Warren 2008, p. 1176).

The effects of water quality impairments on freshwater mussels is well studied (Naimo 1995, entire; Havlik and Marking 1987, entire; Milam et al. 2005, entire; Markich 2017, entire). Contaminants, reduced dissolved oxygen levels, and increased temperatures are primary types of impairments that affect mussel survival, reproduction, and fitness. Freshwater mussels in their early life stages are among the most sensitive organisms to contaminants, but all life stages are vulnerable and can suffer from both acute and chronic effects (Augspurger et al. 2003, p. 2569). Depending on the type and concentration, contaminants can cause mortality of or sublethal effects ( e.g., reduced filtration efficiency, growth, and reproduction) on mussels at all life stages.

In addition to contaminants, alterations in water chemistry, especially reduced dissolved oxygen levels and increased temperatures, can have negative impacts on mussels. Although juveniles tend to be more vulnerable, reduced dissolved oxygen levels can have lethal and sublethal impacts on mussels in all life stages. Mussels require oxygen for metabolism and when levels are low, normal functions and behaviors ( e.g., ventilation, filtration, oxygen consumption, feeding, growth, and reproduction) are impaired. Below a certain level, mortality can occur. Lastly, increased water temperatures can impact mussel health. Young juveniles (less than 3 weeks old) are particularly sensitive, with upper and lower thermal limits 2 to 3 degrees Celsius (°C) higher or lower than juveniles 1 to 2 years older (Martin 2016, pp. 14-17). While drastic increases in temperatures beyond thermal tolerances can cause mortality, the most common negative effects of temperatures on mussels is caused by relatively minor increases that exacerbate impacts caused by other issues, such as contamination. For example, temperature increases impair physiological functions like immune response, filtration and excretion rates, oxygen consumption, and growth (Pandolfo et al. 2012, p. 73). Temperature increases have been linked to increased respiration rates and have also been linked to increased toxicity of some metals, like copper (Rao and Khan 2000, pp. 176-177).

In the Big Canoe Creek watershed, water quality impairments have historically impacted the Canoe Creek clubshell and continue to do so. Rapid habitat assessments conducted from 2008-2013 found 24 of 34 sites to have suboptimal, marginal, or poor habitat and sedimentation and elevated nutrient levels were documented throughout the watershed. For further discussion on water quality impairments within the range of the Canoe Creek clubshell, see the species status assessment report (Service 2020, pp. 35-43). Historically, point source discharges and pesticide and herbicide applications were not well regulated. The Clean Water Act (CWA; 33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq. ) is the primary Federal law in the United States governing water pollution. A primary role of the CWA is to regulate the point source discharge of pollutants to surface waters through a permit process pursuant to the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES). The NPDES permit process may be delegated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to the States. In Alabama, this authority has been delegated to the Alabama Department of Environmental Management. Currently, Alabama Department of Environmental Management requires that discharges not exceed state water quality standards or criteria. However, it has been found that organisms commonly used in toxicity testing for determining water quality criteria may be less sensitive to tested toxicants than some freshwater mussels (Wang et al. 2007). Because there is no information on the Canoe Creek clubshell’s sensitivity to common pollutants, we are not sure whether Federal and State water quality parameters are protective for this species.

The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA; 7 U.S.C. 136 et seq. ) is intended to protect against unreasonable human health or environmental effects. While pesticides are usually tested on standard biological media ( e.g., honey bees ( Apis sp. ), daphnia ( Daphnia magna ), bluegill sunfish ( Lepomis macrochirus ), rainbow trout ( Oncorhynchus mykiss ), mice ( Mus musculus )), often endangered and threatened species are more susceptible to pollutants than test organisms commonly used in bioassays. While State and Federal regulations have become more stringent and toxicity and environmental consequences of contaminants are better understood, the use of many pesticides and herbicides are more commonplace. Runoff and discharges are also concerns now and into the future with the ongoing urbanization of the area.

Climate Events

Climate events such as droughts and floods can have significant impacts on freshwater systems and their fundamental ecological processes (Poff et al. 2002, pp. ii-v). Drought can cause dewatering of freshwater habitats and low flows, which exacerbate water quality impairments ( e.g., dissolved oxygen, temperature, contaminants). Streams with smaller drainage areas are especially vulnerable to drought because they are more likely to experience extensive dewatering than larger streams that maintain substantial flow (Haag and Warren 2008, pp. 1172-1173). Floods can cause excessive erosion, destabilize banks and bed materials, and lead to increases in sedimentation and suspended solids. Climate change can affect the frequency and duration of drought and floods, as well as alter normal temperature regimes. Higher water temperatures, which are common during the low flow periods of droughts, decrease mussel survival (Gough et al. 2012, p. 2363).

Severe drought and major floods can have significant impacts on mussel communities (Haag and Warren 2008, p. 1165; Hastie et al. 2001, p. 107; Hastie et al. 2003, pp. 40-45). Reduced flows from drought can isolate or eliminate areas of suitable habitat for mussels in all life stages and render individuals exposed and vulnerable to drying and predation (Golladay et al. 2004, pp. 503-504). Drought can also degrade water quality ( e.g., decreased dissolved oxygen levels and increased temperatures), which can reduce mussel survival, reproduction, and fitness (Golladay et al. 2004, p. 501; Haag and Warren 2008, pp. 1174-1176) (see discussion above under “Water Quality”). If severe or frequent, droughts can cause substantial declines in mussel abundance. Flooding can also affect mussels by dislodging individuals and depositing them in unsuitable habitat, which can affect their ability to survive and reproduce (Hastie et al. 2001, pp. 108, 114). Higher turbidity and reduced visibility during high flows reduce the chances of successful fertilization of the female and impede the host fish’s ability to find and take up conglutinates.

The stream segments within Big Canoe Creek where clubshells occur have relatively small drainage sizes, which render them particularly vulnerable to drought. Combined with other stressors such as water quality degradation that occur within the watershed, severe droughts can have significant impacts on the species (Haag and Warren 2008, p. 1175). No studies have been conducted specifically on the impacts of drought events to Canoe Creek clubshells within Big Canoe Creek. However, neighboring streams of similar size and condition experienced drastic declines in the density and abundance of the warrior pigtoe ( Pleurobema rubellum, a mussel species similar to the clubshell). Following a severe drought event in 2000, warrior pigtoe abundance declined by 65 to 83 percent (Haag and Warren 2008, p. 1165), and multiple sites were extirpated. We presume that Big Canoe Creek faced similar conditions following this and other severe drought events because of its geographic proximity and similar size and condition. Additionally, we presume the Canoe Creek clubshell’s response to the drought event was comparable to that of the warrior pigtoe given its similar life-history characteristics and physiological and habitat needs.

While the impacts on mussels following the drought in 2000 were well documented (Golladay et al. 2004, entire; Haag and Warren 2008, entire), drought events have been occurring in the area and affecting mussel communities for decades. The severity and frequency of droughts is closely monitored and recorded at the local and State levels by multiple initiatives (NDMC 2019; USGS 2019). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS) program keeps one of the most extensive records (beginning in 1895) of drought in Alabama. The program uses the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI), which is a measurement of dryness based on evapotranspiration (NOAA 2020). These data indicate that over the past 100 years (1918-2018), approximately 6 percent of years experienced severe drought.

While severe droughts are natural events that these streams have always experienced, this part of Alabama has undergone more frequent severe drought events over the last 20 years; the number of severe drought years has increased to approximately 11 percent (NOAA 2020, unpaginated). Water flow gauge data at a Big Canoe Creek gauging site reported low flows that correlate to the severe and exceptional droughts in the Big Canoe Creek watershed during 2000, 2007, and 2008 (USGS 2019). The severe drought events that occurred in relatively short succession during a prolonged dry period likely caused severe impacts to the survival, reproduction, and abundance of Canoe Creek clubshells. Although we do not have specific data on the Canoe Creek clubshell in response to these drought events, the decline of other freshwater mussel species was documented in a nearby watershed. The dark pigtoe ( Pleurobema furvum ), a freshwater mussel with similar life history characteristics of the Canoe Creek clubshell, was extirpated at sites with low densities following the 2000 severe drought event (Haag and Warran 2008, pp. 1173).

Cumulative Effects

It is likely that individual stressors identified are synergistic and have cumulative impacts on the species. For instance, an increase in drought frequency would amplify water quality issues predicted to occur with increases in developed land use. Decreased stream flows would be even less able to accommodate increasing levels of non-point source pollution associated with and expected from increased human populations within the range of the Canoe Creek clubshell. Further, increasing water temperatures from drought events have been and will continue to exacerbate water quality issues such as decreases in dissolved oxygen in Big Canoe Creek (see “Climate Events,” above).

Species Condition

The Canoe Creek clubshell’s ability to withstand, or be resilient to, stochastic events and disturbances such as drought and fluctuations in reproductive rates is extremely limited. The species has likely always been a rare, narrow endemic of the Big Canoe Creek watershed; however, past and ongoing stressors, including decreased water quality from drought events, development, and agriculture, among other sources, have greatly reduced the resiliency of the species. At present, the clubshell has extremely low abundance, shows no signs of successful reproduction, and has poor connectivity within and among subpopulations.

During comprehensive mussel surveys conducted in 2017 and 2018 in the Big Canoe Creek watershed, only 25 Canoe Creek clubshells were found (Fobian et al. 2017, entire; Fobian 2018, entire). In the western subpopulation, 9 individuals were found in 2 of the 40 sites that were surveyed. In the eastern subpopulation, 16 individuals were found at only 1 of the 8 sites that were surveyed. In the 25 years prior to these surveys, fewer than 15 live individuals were found (Fobian et al. 2017, pp. 9-10). Further, the age structure of the individuals located consisted of aged adults and the surveys found no evidence of successful recruitment ( i.e., sub adults (Fobian et al. 2017, pp. 9-10)).

In addition to a low abundance, the clubshell is experiencing recruitment failure; juveniles are not surviving to reproductive ages and joining the adult population (Strayer and Malcom 2012, pp. 1783-1785). This is evidenced by the species’ heavily skewed age class distribution. Of the 25 individuals found in recent surveys, all were aging adults (Fobian et al. 2017, entire; Fobian 2018, entire). This skewed age class distribution is indicative of a species that is not successfully reproducing and is in decline.

Lastly, the resiliency of each subpopulation is limited by their disjunct distribution. The stretch of unsuitable habitat separating the subpopulations prevents individuals from dispersing from one subpopulation to another. This isolation renders the subpopulations vulnerable to extirpation because individuals are unable to recolonize portions of the range following stochastic disturbances that eliminate entire mussel beds or a subpopulation.

The Canoe Creek clubshell’s ability to withstand catastrophic events (redundancy) is also limited, primarily because of its narrow range. Severe droughts resulting in decreased water quality and direct mortality were likely the primary causes of the species’ recent decline. Compared to a more wide-ranging species whose risk is spread over multiple populations across its range, the entirety of the clubshell’s range is impacted by a severe drought event. However, the impacts of other potential catastrophic events, such as contaminant spills, may be restricted to a portion of the clubshell’s range, especially because the species’ subpopulations are not directly downstream from one another.

The ability of the Canoe Creek clubshell to adapt to changing environmental conditions (representation) over time is also likely limited. There are no studies that have explicitly explored the species’ adaptive capacity or the fundamental components—phenotypic plasticity, dispersal ability, and genetic diversity—by which it is characterized. The clubshell is a narrow endemic, inhabiting a single watershed, and we do not observe any ecological, behavioral, or other form of diversity that may indicate adaptive capacity across its range; thus, we presume the species currently has limited ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions.

Future Condition

As part of the SSA, we also developed three future condition scenarios to capture the range of uncertainties regarding future threats and the projected responses by the Canoe Creek clubshell. Our scenarios assumed a moderate or enhanced probability of severe drought, and either propagation or no propagation of the species. Because we determined that the current condition of the Canoe Creek clubshell was consistent with an endangered species (see Determination of Canoe Creek Clubshell’s Status, below), we are not presenting the results of the future scenarios in this rule. Please refer to the SSA report (Service 2020) for the full analysis of future scenarios.

We note that, by using the SSA framework to guide our analysis of the scientific information documented in the SSA report, we have not only analyzed individual effects on the species, but we have also analyzed their potential cumulative effects. We incorporate the cumulative effects into our SSA analysis when we characterize the current and future condition of the species. To assess the current and future condition of the species, we undertake an iterative analysis that encompasses and incorporates the threats individually and then accumulates and evaluates the effects of all the factors that may be influencing the species, including threats and conservation efforts. Because the SSA framework considers not just the presence of the factors, but to what degree they collectively influence risk to the entire species, our assessment integrates the cumulative effects of the factors and replaces a standalone cumulative effects analysis.

Conservation Efforts and Regulatory Mechanisms

State Protections

The Canoe Creek clubshell is currently ranked as a priority 1 (highest conservation concern) species of greatest conservation need in Alabama (Shelton-Nix 2017, p. 51; ANHP 2017, p. 41), but is not currently listed as State threatened or endangered (ADCNR 2015, p. 23, ANHP 2017, p. 41). However, all mussel species not listed as a protected species under the Invertebrate Species Regulation are partially protected by other regulations of the Alabama Game, Fish, and Fur Bearing Animals Regulations. Regulation 220-2-.104 prohibits the commercial harvest of all but the 11 mussel species for which commercial harvest is legal (ADCNR 2015, p. 438). The Canoe Creek clubshell is not one of the 11 mussel species for which commercial harvest is legal.

Conservation Actions

The Service and numerous partners are working to provide technical guidance and offering conservation tools to meet both species and habitat needs in aquatic systems of Alabama. The Big Canoe Creek watershed has been designated as a Strategic Habitat Unit by the Alabama Rivers and Streams Network (a group of non-profit organizations, private companies, State and Federal agencies and concerned citizens that recognize the importance of clean water and working together to maintain healthy water supplies and investigate water quality, habitat conditions, and biological quality in rivers and streams and make these findings to the public) for the purpose of facilitating and coordinating watershed management and restoration efforts as well as focus funding to address habitat and water quality issues (Wynn et al. 2016, p. 11, Wynn et al. 2018, entire). In 2016, the Geological Survey of Alabama completed a watershed assessment of the Big Canoe Creek system for the recovery and restoration of imperiled aquatic species (Wynn et al. 2016, entire). This assessment is being used by multiple Federal, State, and non-government organizations to contribute to restoration projects that will improve habitat and water quality for at risk and listed species like the Canoe Creek clubshell. An example of organizations working together under Alabama Rivers and Streams Network is the removal of the Goodwin’s Mill Dam in 2013 on Big Canoe Creek, which restored connectivity to a portion of the range of the Canoe Creek clubshell within Little Canoe Creek (west). Multiple agencies and groups came together for this removal including: the Service’s Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program, Ecological Services, and Fisheries programs, Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (ADCNR), Geological Survey of Alabama, Alabama Department of Environmental Management, Alabama Power Company, The Nature Conservancy, Coosa River Keeper, and Friends of Big Canoe Creek.

The Nature Conservancy is very active in Alabama and has listed Big Canoe Creek as a priority watershed for focused conservation efforts. The Nature Conservancy has been awarded a National Fish and Wildlife Foundation grant to create a watershed coordinator position for the Big Canoe Creek watershed that will work with landowners on headwater protection through land acquisition and easements; protect water quality by restoring and bolstering riparian buffers on public and private lands; install on the ground restoration projects that stabilize eroding streambanks and increase overall water quality and instream habitat on public and private lands; and promote public access and recreational use of the river through conservation and protection of the water resource. The Nature Conservancy has also received funding from Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Regional Conservation Partnership Program to restore degrading streambanks in several watersheds in Alabama, including the Big Canoe Creek watershed. These efforts are in their early stages and have not yet resulted in improvements to the status of the Canoe Creek clubshell.

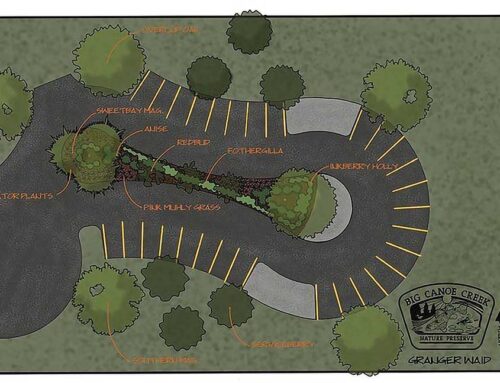

The Friends of Big Canoe Creek is a non-governmental organization formed in 2008 for purpose of preserving and protecting the Big Canoe Creek watershed through education and participation of on the ground conservation efforts that was instrumental in advocating for and nominating land along the creek for inclusion into Forever Wild, a State program that buys land to protect and preserve it. As of 2018, a 382-acre tract of land was established as the Big Canoe Creek Nature Preserve with about a mile of creek frontage near Springville in St. Clair County. The preserve will be retained by the Alabama Land Trust and maintained by the City of Springville. While the Canoe Creek clubshell is not known to occupy the Big Canoe Creek Nature preserve, it is expected that the species will benefit from the habitat protections the preserve provides.

In 2021, the Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center (a program of the ADCNR) submitted a final report detailing aspects of the species’ reproductive periodicity, fish host relationships, and propagation methods. The Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center has been successful in propagating individuals of the species and has begun releasing them into the Big Canoe Creek watershed. In March 2020, approximately 1,500 individuals of the Canoe Creek clubshell were stocked into Big Canoe Creek. Annual monitoring to evaluate growth and survival is planned, and additional propagation and stocking efforts will continue in upcoming years.

In summary, the Canoe Creek clubshell is currently comprised of a critically low number of older adults that are failing to recruit young. The severity and frequency of drought events in the past two decades, combined with other ongoing habitat-related stressors such as sedimentation and water quality degradation and the mussel’s naturally inefficient reproductive strategy, likely caused the decline of the species to its current vulnerable condition. The Canoe Creek clubshell’s vulnerability to ongoing stressors is heightened to such a degree that it is currently on the brink of extinction in the wild as a result of its narrow range and critically low numbers.

Determination of the Canoe Creek Clubshell’s Status

Section 4 of the Act (16 U.S.C. 1533) and its implementing regulations (50 CFR part 424) set forth the procedures for determining whether a species meets the definition of “endangered species” or “threatened species.” The Act defines an “endangered species” as a species that is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range, and a “threatened species” as a species that is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range. The Act requires that we determine whether a species meets the definition of “endangered species” or “threatened species” because of any of the following factors: (A) The present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range; (B) overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; (C) disease or predation; (D) the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; or (E) other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

Canoe Creek Clubshell’s Status Throughout All of Its Range

After evaluating threats to the species and assessing the cumulative effect of the threats under the Act’s section 4(a)(1) factors, we find that past and ongoing stressors including decreased water quality from drought, development, and agriculture, among other sources (Factor A), have reduced the resiliency of the Canoe Creek clubshell to such a degree that the species is particularly vulnerable to extinction. The Canoe Creek clubshell has likely always been a rare, narrow endemic within the Big Canoe Creek, and the species has some natural ability to withstand stochastic demographic fluctuations and catastrophic events such as a severe drought, which are characteristic of the environment in which it evolved. However, the frequency of severe drought events in the past two decades, combined with other ongoing habitat-related stressors and the mussel’s naturally inefficient reproductive strategy, likely caused the decline of the species to its current vulnerable condition from which it is likely unable to recover naturally. The species’ declining trend and tenuous status is evidenced by the results of recent comprehensive surveys in both the western and eastern subpopulations that reveal the species is comprised of a limited number of older adults that are failing to recruit young. We anticipate these threats will continue to act on the species in the future. The Canoe Creek clubshell’s vulnerability to ongoing stressors is heightened as a result of its narrow range and critically low numbers such that it is currently in danger of extinction throughout its range. Thus, after assessing the best available information, we conclude that the Canoe Creek clubshell is in danger of extinction throughout all of its range.

Canoe Creek Clubshell’s Status Throughout a Significant Portion of Its Range

Under the Act and our implementing regulations, a species may warrant listing if it is in danger of extinction or likely to become so in the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range. We have determined the Canoe Creek clubshell is in danger of extinction throughout all of its range and, accordingly, did not undertake an analysis to determine whether there is a significant portion of its range that may have a different status. Because we have determined the Canoe Creek clubshell warrants listing as endangered throughout all of its range, our determination does not conflict with the decision in Center for Biological Diversity v. Everson, 2020 WL 437289 (D.D.C. Jan. 28, 2020), because that decision related to the SPR analyses for a species that warrants listing as threatened, not endangered, throughout all of its range.

Determination of Status

Our review of the best available scientific and commercial information indicates that the Canoe Creek clubshell meets the Act’s definition of an endangered species. Therefore, we are listing the Canoe Creek clubshell as an endangered species in accordance with sections 3(6) and 4(a)(1) of the Act.

Available Conservation Measures

Conservation measures provided to species listed as endangered or threatened species under the Act include recognition, recovery actions, requirements for Federal protection, and prohibitions against certain practices. Recognition through listing results in public awareness, and conservation by Federal, State, tribal, and local agencies, private organizations, and individuals. The Act encourages cooperation with the States and other countries and calls for recovery actions to be carried out for listed species. The protection required by Federal agencies and the prohibitions against certain activities are discussed, in part, below.

The primary purpose of the Act is the conservation of endangered and threatened species and the ecosystems upon which they depend. The ultimate goal of such conservation efforts is the recovery of these listed species, so that they no longer need the protective measures of the Act. Section 4(f) of the Act calls for the Service to develop and implement recovery plans for the conservation of endangered and threatened species. The recovery planning process involves the identification of actions that are necessary to halt or reverse the species’ decline by addressing the threats to its survival and recovery. The goal of this process is to restore listed species to a point where they are secure, self-sustaining, and functioning components of their ecosystems.

Recovery planning consists of preparing draft and final recovery plans, beginning with the development of a recovery outline and making it available to the public subsequent to a final listing determination. The recovery outline guides the immediate implementation of urgent recovery actions and describes the process used to develop a recovery plan. Revisions of the plan may be done to address continuing or new threats to the species, as new substantive information becomes available. The recovery plan also identifies, to the maximum extent practicable, recovery criteria for review of when a species may be ready for reclassification from endangered to threatened (“downlisting”) or removal from protected status (“delisting”), and methods for monitoring recovery progress. Recovery plans also establish a framework for agencies to coordinate their recovery efforts and provide estimates of the cost of implementing recovery tasks. Recovery teams (composed of species experts, Federal and State agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and stakeholders) are often established to develop recovery plans. When completed, the recovery outline, draft recovery plan, and the final recovery plan will be available on our website ( https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/species/4693 ), or from our Alabama Ecological Services Field Office (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT ).

Implementation of recovery actions generally requires the participation of a broad range of partners, including other Federal agencies, States, Tribes, nongovernmental organizations, businesses, and private landowners. Examples of recovery actions include habitat restoration ( e.g., restoration of native vegetation), research, captive propagation and reintroduction, and outreach and education. The recovery of many listed species cannot be accomplished solely on Federal lands because their range may occur primarily or solely on non-Federal lands. To achieve recovery of these species requires cooperative conservation efforts on private, State, and Tribal lands.

Following publication of this final rule, funding for recovery actions will be available from a variety of sources, including Federal budgets, State programs, and cost-share grants for non-Federal landowners, the academic community, and nongovernmental organizations. In addition, pursuant to section 6 of the Act, the State of Alabama would be eligible for Federal funds to implement management actions that promote the protection or recovery of the Canoe Creek clubshell. Information on our grant programs that are available to aid species recovery can be found at: https://www.fws.gov/service/financial-assistance.

Please let us know if you are interested in participating in recovery efforts for the Canoe Creek clubshell. Additionally, we invite you to submit any new information on this species whenever it becomes available and any information you may have for recovery planning purposes (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT ).

Section 7(a) of the Act requires Federal agencies to evaluate their actions with respect to any species that is proposed or listed as an endangered or threatened species and with respect to its critical habitat, if any is designated. Regulations implementing this interagency cooperation provision of the Act are codified at 50 CFR part 402. Section 7(a)(2) of the Act requires Federal agencies to ensure that activities they authorize, fund, or carry out are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered or threatened species or destroy or adversely modify its critical habitat. If a Federal action may affect a listed species or its critical habitat, the responsible Federal agency must consult with the Service.

Federal agency actions within the species’ habitat that may require consultation, as described in the preceding paragraph include management and any other landscape-altering activities. These actions include, but are not limited to, work authorized by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that administers the issuance of section 404 Clean Water Act permits that regulate fill of wetlands and the Federal Highway Administration that regulates the construction and maintenance of roads or highways. Additional actions that may require consultation are those conducted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program. This program provides technical and financial assistance to private landowners and Tribes who are willing to help meet habitat needs of Federal trust species. The Farm Service Agency administers the Conservation Reserve Program, which includes providing incentives for farmers and private landowners to use their environmentally sensitive agricultural land for conservation benefit. The Natural Resources Conservation Service works with private landowners under multiple Farm Bill programs, all aimed at the conservation of water and soil.

The Act and its implementing regulations set forth a series of general prohibitions and exceptions that apply to endangered wildlife. The prohibitions of section 9(a)(1) of the Act, codified at 50 CFR 17.21, make it illegal for any person subject to the jurisdiction of the United States to take (which includes harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect; or to attempt any of these) endangered fish or wildlife within the United States or on the high seas. In addition, it is unlawful to import; export; deliver, receive, carry, transport, or ship in interstate or foreign commerce in the course of commercial activity; or sell or offer for sale in interstate or foreign commerce any species listed as an endangered species. It is also illegal to possess, sell, deliver, carry, transport, or ship any such wildlife that has been taken illegally. Certain exceptions apply to employees of the Service, the National Marine Fisheries Service, other Federal land management agencies, and State conservation agencies.

We may issue permits to carry out otherwise prohibited activities involving endangered wildlife under certain circumstances. Regulations governing permits are codified at 50 CFR 17.22. With regard to endangered wildlife, a permit may be issued for the following purposes: For scientific purposes, to enhance the propagation or survival of the species, and for incidental take in connection with otherwise lawful activities. There are also certain statutory exemptions from the prohibitions, which are found in sections 9 and 10 of the Act.

It is our policy, as published in the Federal Register on July 1, 1994 (59 FR 34272), to identify to the maximum extent practicable at the time a species is listed, those activities that would or would not constitute a violation of section 9 of the Act. The intent of this policy is to increase public awareness of the effect of a listing on proposed and ongoing activities within the range of the listed species. Based on the best available information, the following actions are unlikely to result in a violation of section 9, if these activities are carried out in accordance with existing regulations and permit requirements; this list is not comprehensive:

(1) Normal agricultural and silvicultural practices, including herbicide and pesticide use, that are carried out in accordance with any existing regulations, permit and label requirements, and best management practices.

(2) Normal residential development and landscape activities that are carried out in accordance with any existing regulations, permit requirements, and best management practices.

(3) Normal recreational hunting, fishing, or boating activities that are carried out in accordance with all existing hunting, fishing, and boating regulations, and following reasonable practices and standards.

Based on the best available information, the following activities, which are activities that the Service finds could potentially harm the Canoe Creek clubshell and result in “take” of the species, may potentially result in a violation of section 9 of the Act if they are not authorized in accordance with applicable law; this list is not comprehensive:

(1) Unauthorized collecting, handling, possessing, selling, delivering, carrying, or transporting of the Canoe Creek clubshell, including import or export across State lines and international boundaries, except for properly documented antique specimens of the taxon at least 100 years old, as defined by section 10(h)(1) of the Act.

(2) Unauthorized modification of the channel, substrate, temperature, or water flow of any stream or water body in which the Canoe Creek clubshell is known to occur.

(3) Unauthorized discharge of chemicals or fill material into any waters in which the Canoe Creek clubshell is known to occur.

(4) Introduction of nonnative species that compete with or prey upon the Canoe Creek clubshell, such as the zebra mussel ( Dreissena polymorpha ) and Asian clam ( Corbicula fluminea ).

(5) Pesticide applications in violation of label restrictions.

Questions regarding whether specific activities would constitute a violation of section 9 of the Act should be directed to the Alabama Ecological Services Field Office (see FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT ).

II. Critical Habitat

Background

Critical habitat is defined in section 3 of the Act as:

(1) The specific areas within the geographical area occupied by the species, at the time it is listed in accordance with the Act, on which are found those physical or biological features

(a) Essential to the conservation of the species, and

(b) Which may require special management considerations or protection; and

(2) Specific areas outside the geographical area occupied by the species at the time it is listed, upon a determination that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species.

Our regulations at 50 CFR 424.02 define the geographical area occupied by the species as an area that may generally be delineated around species’ occurrences, as determined by the Secretary ( i.e., range). Such areas may include those areas used throughout all or part of the species’ life cycle, even if not used on a regular basis ( e.g., migratory corridors, seasonal habitats, and habitats used periodically, but not solely by vagrant individuals).

Conservation, as defined under section 3 of the Act, means to use and the use of all methods and procedures that are necessary to bring an endangered or threatened species to the point at which the measures provided pursuant to the Act are no longer necessary. Such methods and procedures include, but are not limited to, all activities associated with scientific resources management such as research, census, law enforcement, habitat acquisition and maintenance, propagation, live trapping, and transplantation, and, in the extraordinary case where population pressures within a given ecosystem cannot be otherwise relieved, may include regulated taking.

Critical habitat receives protection under section 7 of the Act through the requirement that Federal agencies ensure, in consultation with the Service, that any action they authorize, fund, or carry out is not likely to result in the destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat. The designation of critical habitat does not affect land ownership or establish a refuge, wilderness, reserve, preserve, or other conservation area. Designation also does not allow the government or public to access private lands, nor does designation require implementation of restoration, recovery, or enhancement measures by non-Federal landowners. Where a landowner requests Federal agency funding or authorization for an action that may affect a listed species or critical habitat, the Federal agency would be required to consult with the Service under section 7(a)(2) of the Act. However, even if the Service were to conclude that the proposed activity would result in destruction or adverse modification of the critical habitat, the Federal action agency and the landowner are not required to abandon the proposed activity, or to restore or recover the species; instead, they must implement “reasonable and prudent alternatives” to avoid destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat.

Under the first prong of the Act’s definition of critical habitat, areas within the geographical area occupied by the species at the time it was listed are included in a critical habitat designation if they contain physical or biological features (1) which are essential to the conservation of the species and (2) which may require special management considerations or protection. For these areas, critical habitat designations identify, to the extent known using the best scientific and commercial data available, those physical or biological features that are essential to the conservation of the species (such as space, food, cover, and protected habitat). In identifying those physical or biological features that occur in specific occupied areas, we focus on the specific features that are essential to support the life-history needs of the species, including, but not limited to, water characteristics, soil type, geological features, prey, vegetation, symbiotic species, or other features. A feature may be a single habitat characteristic or a more complex combination of habitat characteristics. Features may include habitat characteristics that support ephemeral or dynamic habitat conditions. Features may also be expressed in terms relating to principles of conservation biology, such as patch size, distribution distances, and connectivity.

Under the second prong of the Act’s definition of critical habitat, we can designate critical habitat in areas outside the geographical area occupied by the species at the time it is listed, upon a determination that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species. The implementing regulations at 50 CFR 424.12(b)(2) further delineate unoccupied critical habitat by setting out three specific parameters: (1) when designating critical habitat, the Secretary will first evaluate areas occupied by the species; (2) the Secretary will only consider unoccupied areas to be essential where a critical habitat designation limited to geographical areas occupied by the species would be inadequate to ensure the conservation of the species; and (3) for an unoccupied area to be considered essential, the Secretary must determine that there is a reasonable certainty both that the area will contribute to the conservation of the species and that the area contains one or more of those physical or biological features essential to the conservation of the species.

Section 4 of the Act requires that we designate critical habitat on the basis of the best scientific data available. Further, our Policy on Information Standards Under the Endangered Species Act (published in the Federal Register on July 1, 1994 (59 FR 34271)), the Information Quality Act (section 515 of the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2001 (Pub. L. 106-554; H.R. 5658)), and our associated Information Quality Guidelines provide criteria, establish procedures, and provide guidance to ensure that our decisions are based on the best scientific data available. They require our biologists, to the extent consistent with the Act and with the use of the best scientific data available, to use primary and original sources of information as the basis for recommendations to designate critical habitat.

When we are determining which areas should be designated as critical habitat, our primary source of information is generally the information from the SSA report and information developed during the listing process for the species. Additional information sources may include any generalized conservation strategy, criteria, or outline that may have been developed for the species; the recovery plan for the species; articles in peer-reviewed journals; conservation plans developed by States and counties; scientific status surveys and studies; biological assessments; other unpublished materials; or experts’ opinions or personal knowledge.

Habitat is dynamic, and species may move from one area to another over time. We recognize that critical habitat designated at a particular point in time may not include all of the habitat areas that we may later determine are necessary for the recovery of the species. For these reasons, a critical habitat designation does not signal that habitat outside the designated area is unimportant or may not be needed for recovery of the species. Areas that are occupied by the species and important to the conservation of the species, both inside and outside the critical habitat designation, will continue to be subject to: (1) Conservation actions implemented under section 7(a)(1) of the Act; (2) regulatory protections afforded by the requirement in section 7(a)(2) of the Act for Federal agencies to ensure their actions are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any endangered or threatened species; and (3) the prohibitions found in section 9 of the Act. Federally funded or permitted projects affecting listed species outside their designated critical habitat areas may still result in jeopardy findings in some cases. These protections and conservation tools will continue to contribute to recovery of this species. Similarly, critical habitat designations made on the basis of the best available information at the time of designation will not control the direction and substance of future recovery plans, habitat conservation plans (HCPs), or other species conservation planning efforts if new information available at the time of these planning efforts calls for a different outcome.

Physical or Biological Features Essential to the Conservation of the Species

In accordance with section 3(5)(A)(i) of the Act and regulations at 50 CFR 424.12(b), in determining which areas we will designate as critical habitat from within the geographical area occupied by the species at the time of listing, we consider the physical or biological features that are essential to the conservation of the species and that may require special management considerations or protection. The regulations at 50 CFR 424.02 define “physical or biological features essential to the conservation of the species” as the features that occur in specific areas and that are essential to support the life-history needs of the species, including, but not limited to, water characteristics, soil type, geological features, sites, prey, vegetation, symbiotic species, or other features. A feature may be a single habitat characteristic, or a more complex combination of habitat characteristics. Features may include habitat characteristics that support ephemeral or dynamic habitat conditions. Features may also be expressed in terms relating to principles of conservation biology, such as patch size, distribution distances, and connectivity.

For example, physical features essential to the conservation of the species might include gravel of a particular size required for spawning, alkaline soil for seed germination, protective cover for migration, or susceptibility to flooding or fire that maintains necessary early-successional habitat characteristics. Biological features might include prey species, forage grasses, specific kinds or ages of trees for roosting or nesting, symbiotic fungi, or a particular level of nonnative species consistent with conservation needs of the listed species. The features may also be combinations of habitat characteristics and may encompass the relationship between characteristics or the necessary amount of a characteristic essential to support the life history of the species. In considering whether features are essential to the conservation of the species, the Service may consider an appropriate quality, quantity, and spatial and temporal arrangement of habitat characteristics in the context of the life-history needs, condition, and status of the species. These characteristics include, but are not limited to, space for individual and population growth and for normal behavior; food, water, air, light, minerals, or other nutritional or physiological requirements; cover or shelter; sites for breeding, reproduction, or rearing (or development) of offspring; and habitats that are protected from disturbance.

Canoe Creek clubshells live in freshwater rivers and streams. Clubshells, like many other freshwater mussels, live in aggregations called mussel beds, which can be patchily distributed throughout an occupied river or stream reach, but together comprise a mussel population. Mussel beds are connected to one another when host fish infested by mussel larvae in one bed disperse the larvae to another bed. While adults are mostly sedentary, larval dispersal among beds causes mussel density and abundance to vary dynamically throughout an occupied reach over time. Connectivity among beds and populations is essential for maintaining resilient populations because it allows for recolonization of areas following stochastic events. Populations that do not occupy a long enough reach or have too few or sparsely distributed beds are vulnerable to extirpation.